by Mercy Austin, staff writer

On Thursday, March 17 from 3-4:40, PPCC hosted a virtual speaker panel featuring experts on children’s literature and local politics to discuss challenges libraries and schools often face regarding censorship and children’s access to media.

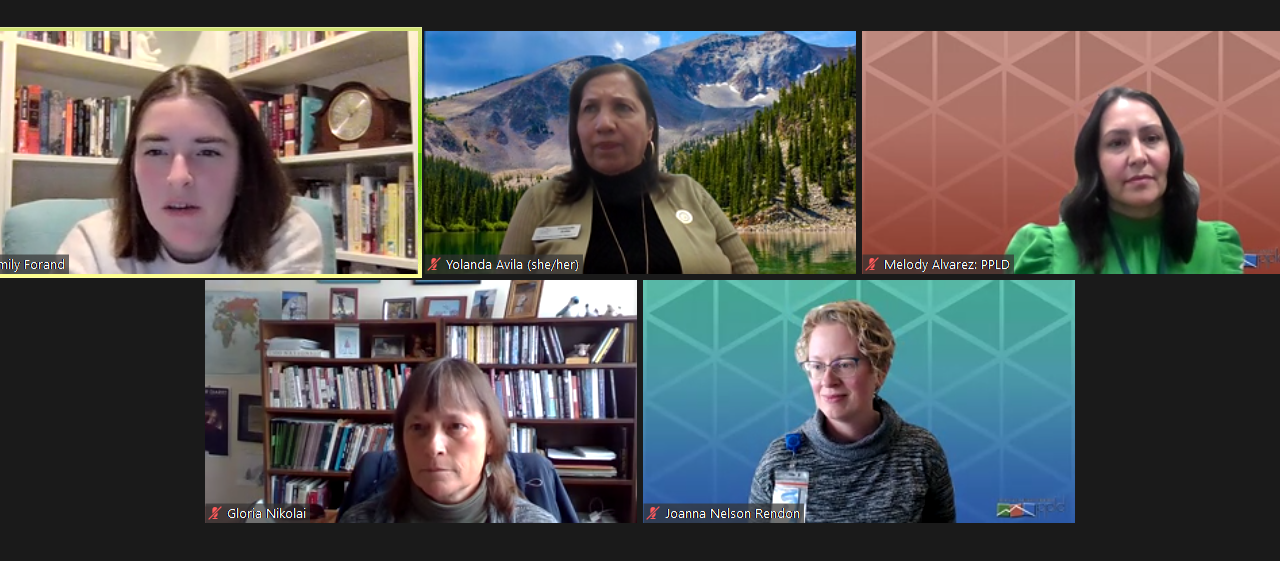

There were four panelists:

- Yolanda Avila: Colorado Springs City-Councilmember

- Melody Alvarez: Director of Family and Children’s Services, Pikes Peak Library District

- Joanna Nelson Rendon: Director of Young Adult Services, Pikes Peak Library District

- Gloria Nikolai: PPCC Professor of Sociology

PPCC Associate Professor of English Emily Forand led the discussion. Topics included children’s right to readership, the role of public libraries, the history behind which books tend to be challenged, the relationship between banned books and diverse books, and much more.

Recent national and local controversies have put children’s literature in the spotlight. In Richland, Mississippi, city mayor Gene McGee withheld $110,000 in funding from local libraries unless they removed books related to “homosexual content.” Similarly, a school district in St. Louis, Missouri was sued by the American Civil Liberties Union for removing books from school libraries that discussed race, sexuality, and gender identity. These examples represent a few cases among hundreds—discussions about censorship are raging across the country.

In Colorado Springs, recent elections have enlivened the controversy in local schools and libraries. Yolanda Avila, who serves as Vice President of the District 4 City Council and is on the Harrison County School Board, noted that many community leaders are vocal about the questions this topic raises. Wayne Vanderschuere, a former member of the Pikes Peak Library District (PPLD) board, was recently bypassed for reappointment after his defense of the inclusion of controversial media in the catalogue.

Aaron Salt, a PPLD board member who is newly elected following Vanderschuere’s removal, announced his intention to remove books he considers age inappropriate from the children’s and juvenile sections. He has not offered specific titles.

In light of the controversy, John Spears, who served PPLD as the chief librarian and CEO since 2016, announced in February that he was stepping down. In a statement to the Colorado Springs Indy, he said, “It is my hope that the values that define a library such as freedom of expression, freedom of thought, and freedom of speech will continue to be honored. I look forward to moving to a community where they are not under threat.”

Walk Two Moons by Sharon Creech

Forand, who teaches Children’s Literature classes at PPCC, has experienced backlash towards her own curriculum. One book, Walk Two Moons by Sharon Creech, was removed after years of teaching because of “stick figures hanging, cursing and miscarriage, hysterectomy/stillborn, and screaming during labor,” Forand said. The story follows a 13-year-old girl with Native American roots going on a road-trip with her grandparents and telling stories of her childhood.

For Forand, the book’s departure represents a troubling trend of underestimating what children are prepared to handle. “Behind these glib reasons for banning children’s books often lie some beautiful stories about the human experience. As we toss the entire novel out for some small aspect of its story, I’m afraid this will become a slippery slope in all literature,” she said.

Not my Idea: A Book about Whiteness by Anastasia Higginbotham

The panel discussed the removal of Walk Two Moons, as well as other books that received recent backlash, such as Not My Idea: A Book about Whiteness by Anastasia Higginbotham, which was challenged at PPLD last November for “critical race theory” but ultimately kept on the catalogue.

Librarians deal with serious questions about where to draw the line between “children’s” and “adult” literature. What does “age appropriate” entail, and who should be the arbiter of what is acceptable? Can topics like divorce, abuse, or alcohol be prevalent in a children’s book, given that these are real issues many children face? What role do parental rights play?

Melody Alvarez, director of family and children’s services at PPLD, believes it’s important to err on the side of inclusion. “When they read these books, children see ‘I’m not alone, something’s not wrong with me.’ We want to make sure we provide the materials to give them that opportunity,” she said. She argues that if these resources are removed, kids will turn to the internet or their peers, where information is less monitored and reliable.

One of the most prevalent topics discussed at the panel was the intersection between challenged books and books that relate to diverse and minoritized communities. Joanna Nelson Rendon, director of Young Adult services at PPLD, shared that the most common reasons given for book challenges are Critical Race Theory and LGBTQ+ content, which is in keeping with larger national trends. Annual reports from the National Library Association concluded that in 2019, challenges related to LGBTQ+ content made up 8 out of the 10 most banned books, and in 2020, 6 out of the 10 dealt with race or included a main character of color.

These numbers stand out due to the existing lack of diversity within Children’s Literature. One study from the Cooperative Children’s Book Center indicated that only 3.1% of all children’s books have a protagonist who is LGBTQ+, and less than 30% have one who is a person of color.

Forand cited the work of Emily Knox, an associate professor at The University of Illinois at Urbana-Champagne and the author of Book Banning in 21st Century America. In an article with the School Library Journal, Knox made the argument that censorship is often used as a mechanism to silence minority people groups: “Diverse books, by definition, center of the experiences of people who are not dominant in society, and these stories include experiences that may make the reader uncomfortable in some way,” she said. For Knox, banning diverse literature is a form of marginalizing children, many of whom undergo a myriad of experiences that they aren’t allowed to read about for being too “adult.”

Avila suggested that these attitudes could be in part due to the fact that only one member of PPLD’s board is a person of color. She emphasized the importance of electing board members who will uphold diverse values and champion better representation in literature.

“Censorship thrives on silence,” said Alvarez; “We need to speak up to make sure libraries have materials for everyone. We know who we’re representing in our communities and our collection policy should reflect that.’